Time, the Rabbis, and Poetry

As secular years end and begin while the Jewish year continues, here are some reflections on Jewish notions of time, the content of the last final paper of the fall semester.

Judaism is a religion of place—the claim to the Land of Israel is woven into its narrative of redemption—and of time.

While the notion of place may at first sight seem one-dimensional, limited to a specific stretch of tangible soil in the Levant, the notion of time presents itself multilayered throughout, from Torah to rabbinic discussions about its nature; how to measure and relate to time; and what implications time has for Judaism’s system of religious observance.

Non-orthodox Jews today, who primarily look to making Judaism relevant to matters at hand, prioritize the religion’s ethical and social justice imperatives that focus on the immediacy of the present: אם לא עכשיו אימתי?: When, if not now? asks Rabbi Hillel[1]: Here, conjunctions of time express the command to act and take responsibility on the continuum of generations that have applied themselves to making “the world” - human society - a better, more just, more sustainable, more peaceful place: לא עליך המלאכה לגמר, ולא אתה בן חורין לבטל ממנה: It is not your duty to finish the work, but neither are you at liberty to neglect it[2].

This oft-quoted adage attributed to Rabbi Tarfon expresses on the surface a practical approach to time and its passing. As such, it is often understood, like the wisdom of Rabbi Hillel, as an elevator pitch ofתיקון עולם on one foot.

But both Hillel and Tarfon represent merely aspects of Tikkun Olam, whose larger theological meaning transcends social justice efforts, non-negotiable as they are for human society.

In the Aleinu prayer, the term Tikkun Olam takes on a decidedly theological meaning that points toward a more transcendental concept of time in Judaism:

על כן נקוה לך יהוה אלהינו לראות מהרה בתפארת עזך להעביר גלולים מן הארץ והאלילים כרות יכרתון לתקן עולם במלכות שדי וכל בני בשר יקראו בשמך, להפנות אליך כל רשעי ארץ, יכירו וידעו כל יושבי תבל כי לך תכרע כל ברך תשבע כל לשון

Therefore, we place our hope in You, Lord our God, that we may soon see the glory of Your power, when You will remove abominations from the earth, and idols will be utterly destroyed, when the world will be perfected under the sovereignty of the Almighty, when all humanity will call on Your name, to turn all the earth’s wicked toward You. All the world’s inhabitants will realize and know that to You every knee must bend, and every tongue swear loyalty.

Tikkun Olam in the Aleinu prayer refers to a future perfected world as a world in which all humanity will worship the Jewish God, echoing the prophet Zechariah’s eschatological vision of the day of the coming of the Lord with all holy beings, a day that will do away with “the wicked” but that also ends time as a phenomenon that affects humans[3]. On that day, the prophet says, “there shall be neither sunlight nor cold moonlight, but there shall be a continuous day—only God knows when—of neither day nor night, and there shall be light at eventide.”[4]

Terms like “eschatological vision”; the “day / coming of the Lord”; “redemptive or Messianic age”; or “the World-to-Come” are not entirely interchangeable, but what they all share is the anticipation of time being suspended, an age when and where time no longer has any power over the human realm, when humans will be as unaffected by the continuum of days and nights and years as God is.

This longing for being outside of, or unaffected by, time is famously expressed in the notion of Shabbat as being outside of time – what Abraham Joshua Heschel has called a “cathedral in time” - and it makes sense, then, that Shabbat is understood by the rabbis as a taste, or 1/60th of the World-to-Come.[5]

It can therefore be said that Judaism is shaped by at least two notions of time that have overlapping theological implications: The first is the orientation toward the “here and now” and contains an obligation to bring more justice to the life of humans in the world. The second one aims toward a goal at the end of a timeline. It will bring God’s eternal reign over all humans, who will be subsumed into and become one with God’s timeless quality and domain: לעולם ועד – the word עולם does double-duty: God’s world will exist forever and ever.

There is a third aspect I find noteworthy. This one, while still concerned with theological implications is a poetic and chronological paradox: When Judaism looks ahead, it also looks back. This is evident in appeals to God to “renew our days as of old”[6] that are prevalent throughout the Jewish liturgy. The past is evoked as something to return to and to renew (and, echoing Rabbi Avraham Yitzchak Kook’s statement, to make holy), as a former ideal to live up to in the future, thus bending the teleological movement of the Jewish redemption narrative onward into a spiral.

Related to this confluence of backward and forward is Judaism’s eastward orientation. from which emerges a confluence of time and place: ולפאתי מזרח קדימה, goes a line in Israel’s national anthem - forward, toward the east, yearns the Jewish soul, eyes turned to Zion.

East here of course is a place - the land, Zion, Jerusalem. But east arguably also connotes time: East is the cardinal direction of the past, the days of old and simultaneously, it is the cardinal direction of renewal. Generally, the hero’s journey in Western ideologies and myths leads toward the setting sun and ends there. Judaism is very distinct. While Abraham did migrate toward the west, not unlike a Manifest Destiny pioneer, Judaism clearly looks toward the rising sun emerging from behind the Mount of Olives, from the east, anticipating an eternal restoration and sanctification of the paradisiacal light emanating from the eastern point of the Fertile Crescent.

Built into the narrative of redemption are both lines from a given point A to a given point B: from Ur-Chasdim to the Land of Canaan, from the Land of Canaan to Egypt, from Egypt to the Land of Israel. Additionally, a cyclical movement occurs as well: No major section of Tanakh ends with the Israelites settled in the land, at sunset, as it were. The people are always and again making their way back to it - until the redemptive or Messianic age, when the light from the east will absorb not only straight lines and spirals, but when the tangibility of a geographic place will drip and melt[7] into the paradisiacal “geography” of Gan Eden.

All these three notions of time bring up theological questions of God’s nature and of God’s relationship to time.

“The question of whether God exists in time, and how divine time relates to human time, animated the theological work of many ancient thinkers,” writes Sarit Kattan Gribetz[8]:

“Philo of Alexandria, for example, argued in his treatise on the creation of the world that, in contrast to people and all other creations, God exists out of time and that this timeless aspect of the divine differentiates the divine from the human.”

Similarly, the Rambam, despite his refusal to make positive statements about the nature of God, held that God existed outside of time. The fourth of the Rambam’s thirteen principles of faith states: “God existed prior to all else[9].”

If God, as Maimonides contends, is uncreated and exists outside of time, God inhabits incorporeal eternity. God’s atemporality distinguishes God, the divine realm, from the human realm, since humans are created and bound by time. Mortal bodies, they don’t inhabit eternity. “Time, then distinguishes, and even defines the difference between divine and human,”[10] writes Kattan Gribetz. The experience of and relation to time defines the difference between this world and the World-to-Come.

There is another question that arises when God is atemporal and humans are bound by temporality: In what way does God’s existence matter to humans - or why would humans matter to God? In her chapter about “Human and Divine Time,” Kattan Gribetz shows how the rabbis, in trying to make the relationship between God and humans relevant, instituted the idea of God as being both outside of time – and yet fully involved with human time.

“In rabbinic texts, both humans and God exist in time – and indeed in the same time. People, right along with God, reckon time according to the same seven-day week, daily hours, nightly watches, midnight, and other subdivisions of the day. God also uses time to engage in activities with which humans occupy themselves. In rabbinic sources, time thus functions to connect humans and God within a shared temporal system. But time also functions to distinguish between humans and God in rabbinic texts. For while rabbinic sources present God as existing in time, they also suggest that God has a different relationship to time than humans do. God has days, nights, and hours, but God’s time never ends (…).”[11]

In the same chapter, Kattan Gribetz continues to examine specific examples from rabbinic literature about how God is seen to spend God’s time, gesturing toward an anthropomorphic conception of God in human time. Many of these examples are, not surprisingly, related to God’s capacity of creation – a prime example of divine activity described in units of time – six days and a seventh – that are accessible to the human experience.

***

Moving away from these broader theological concepts, I now want to turn to examples of the role time plays in the everyday practice of Judaism.

An awareness of time – or rather of the movement of light in the sky – is essential to traditional Jewish observance. In fact, to mark the passage of time is the first mitzvah in Torah:

ויאמר יהוה אל־משה ואל־אהרן בארץ מצרים לאמר

החדש הזה לכם ראש חדשים ראשון הוא לכם לחדשי השנה

YHWH said to Moses and Aaron in the land of Egypt: This month shall mark for you the beginning of the months; it shall be the first of the months of the year for you.[12]

From this first month, the occurrence of all other holidays is determined. Establishing a calendar is essential to keep track of the seasons and to ensure that worship and festivals are celebrated at the right, divinely ordained times. This demands for reliable ways to measure time. Knowing the exact time is crucial for traditional observance, as the hours and minutes of the day determine when to say certain prayers, when Shabbat begins and ends, and how to define a baby’s Hebrew date of birth[13].

Today, the זמנים are easily accessible online or in a synagogue’s newsletter. But how could time be measured in an era without clocks or astronomical instruments?

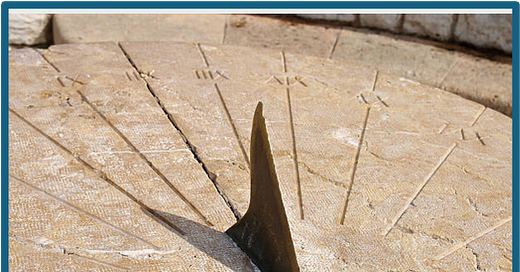

Lynn Kaye explores this question in “Time in the Babylonian Talmud: Natural and Imagined Times in Jewish Law and Narrative.” Like Kattan Gribetz[14], she mentions the – very limited – usage of sundials in Roman Palestine as a new method to “tell the time.”

“Most people judged the time of day by reference to natural processes and social rhythms. Roman elite, leisured classes, on the other hand, did consult sundials. There are also mentions of wealthy people sending their slaves out in order to ascertain and report the hour of the day. Yet there is no evidence from Roman sources of farm workers or shopkeepers marking their days in such ways. For example, gladiatorial contests in ancient Rome listed no starting times; people simply arrived. The same was likely true for non-aristocratic Jews in Roman Judea and the Galilee. Although sundials were available in temple sites and palaces, ordinary people did not likely have ongoing and regular opportunities to consult them.”[15]

Kaye’s point is to show that without regular access to somewhat reliable time-keeping devices, people in late Antiquity in general and the Talmudic sages in particular had to come up with alternative ways to measure time, and, maybe even more significantly, to describe time.

“This book argues that the Bavli produces sophisticated and innovative portrayals of temporality, and that its legal and narrative reasoning is based on its authors’ temporal premises. (…) In contrast to what is known about calendrical calculations and time-measurement, relatively little is known about the temporal imagination of the Talmudic rabbis. The focus of this book is on that elusive temporal imagination.”[16]

Although today, astronomical instruments allow humans to come as close to divine timely precision as never before, traditional observance in diaspora communities is still influenced by the erstwhile lack of accurate and ubiquitous time-keeping devices in rabbinic times: For example, to this day, yom tov sheini is largely observed because determination of the new moon depended on eyewitnesses who had to observe the first sliver in the sky, travel to the rabbinic court, deliver testimony, and be accepted as trustworthy[17] before the announcement of the new month could be declared and spread to all communities near and far, inevitably widening the timely distance between the sighting and the marking of the new moon.

Thus, the institution of the second day of most festivals as largely a security measure to “get it right” admits to the arbitrariness and inadequacy of human efforts in timekeeping. The story about Rabbi Yehoshua and Rabban Gamliel and their disagreement about the calculation of the new moon of Tishrei[18] is another example: As long as there needs to be an extra day added “just in case”, or as long as disagreements exist between sages about the exact beginning of the new year, even if one sage is forced to concede to the other, timely precision is revealed as a distinctively divine attribute, since humans inevitably fail. Therefore, writes Kaye, “the Bavli assumes that human beings observe hours and times broadly; they are not expected to mark times of day with precision.”[19] This assumption is manifest in many deeply poetic sugyiot throughout the Talmud, for example in the iconic opening pages of the Talmud in Tractate Berakhot. In the context of this paper, it is fitting that the official, albeit haphazard, beginning of rabbinic literature is a question about time: מאימתי קורין את שמע בערבית - From when on does one recite Shema in the evening[20]?

The rabbinic answers diverge quickly into a spectrum of options, but not of “from when on” but of “until when,” which requires the Gemara to discuss the characteristics of either different phases of the night – in the first segment, a donkey brays, in the second, a dog barks and in the third, a baby nurses from the mother’s breast - or different shades of light while dawn breaks.[21] Is dawn breaking when one can distinguish between sky-blue and leek-green? Or when one can recognize the face of an acquaintance from six foot apart? The observant Jew needs to know, because the orchestration of when the say certain prayers depends on these minutiae. Simultaneously, these constitute beautiful examples that are both elusive, poetic – and very much rooted in an intimate familiarity with the rhythm of daily human life: Telling the time, here, is defining, telling, what happens in the world – like a bard, or poet.

Kaye gives another example that illustrates the connection between individual and collective experience and imagination as a basis for keeping track of time’s passage:

“Rabbinic texts include a variety of measurements of time related to walking, such as the time it takes to walk a half-mil or knowing the length of twilight by the amount of time it would take for a man to descend from a particular mountain, bathe in the sea, and return. Not only can a distance describe a specific time period, but conversely, a specific time period can express a distance. B. Hagigah 13a describes the distance between the earth and the heavens as a “five hundred years’ walk.” Clearly, the interrelation between the temporal and the spatial is a feature of rabbinic legal thinking, but it is important to note that the conceptual interdependence of the spatial, temporal, and kinesthetic extends beyond the realm of measurement.”[22]

The sundials of late antiquity are today’s clocks. And neither rabbinic sage nor poet could be satisfied with the notion that, in order to tell and describe the time, it suffices to consult mechanical devices. Like poets, the rabbis knew that the nature of time might be best described with that which eludes our grasp and complete understanding, with what we can only express in images or feelings. In the below excerpt from “On Some Other Planet, You May be Right,”[23] the Israeli poet Yehuda Amichai gestures, like Lynn Kaye, toward the immeasurableness of time.

“Look, just as time isn’t inside clocks

love isn’t inside bodies:

bodies only tell the love.

But we will remember this evening

the way swimmers remember the strokes

from one summer to the next.”

These last lines could be in the Talmud, and I am sure that had the rabbis been able to read this poem, they would have resonated with it. In this instance, time – both a specific point in time as well as the ever-lengthening distance from it – is remembered[24] as a state of in-between[25].

In this short excerpt from Amichai’s poem, all three notions of Jewish time as I have sketched them out in the beginning of this paper, are present: We carry within us the memory of and the longing for a time that was and that will return, again, and again, and that maybe, eventually, last eternally. In the meantime, we live in the in-between: in the present that in every moment is a bridge between the past and the future.

[1]Pirkei Avot 1:14

[2] Pirkei Avot 2:16

[3] Zecharia 14

[4] Zecharia 14:6-7 והיה ביום ההוא לא־יהיה אור יקרות וקפאון והיה יום־אחד הוא יודע ליהוה לא־יום ולא־לילה והיה לעת־ערב יהיה־אור

[5] B. Berakhot 57b

[6] For example, at the end of the Torah service, quoting the (second to) last verse from Eicha, 5:21

[7] Amos 9:13 or Psalm 97:5

[8] Sarit Kattan Gribetz: Time and Difference in Rabbinic Judaism, Princeton 2020, page 189

[9] This also touches on questions about creatio ex nihilo which won’t be discussed here.

[10] Kattan Gribetz, page 189

[11] Kattan Gribetz, page 190

[12] Exodus 12:1

[13] If the baby is born between dusk and nightfall, at twilight, in the in-between. See footnote 25

[14] Pages 192-194

[15] Lynn Kaye: Time in the Babylonian Talmud: Natural and Imagined Times in Jewish Law and Narrative,

Cambridge 2018, Chapter 2 (online book)

[16] Kaye, Intro

[17] M. Rosh Hashanah 2:6

[18] M. Rosh Hashana 2:9

[19] Kaye, Chapter 2

[20] M. Berakhot 1:1

[21] B. Berakhot 3a and 9b

[22] Kaye, Chapter 1. This is where time and place merge into “space”: When we determine a timespan in distances or travel time, then we facture in the movement of the sun in the sky – and the religious practice becomes three-dimensional.

[23] In: Robert Alter (editor): The Poetry of Yehuda Amichai, Farrar, Straus and Giroux 2015, page 309

[24] The role and understanding of memory as a device to keep track of time belongs, here but can’t be expanded on in this paper.

[25] The notion of life as in-between times, in between realms – in the twilight (בין השמשות) is prevalent in Torah as well as in Talmud. Kaye writes in her introduction: “Imagining time as what is in-between, connecting events together in multiple configurations, implies a spatial image of temporality” – also the subject of a separate paper.

Julia, Yasher Koach! Lovely discussion.